Ed. Comment

While I have some disagreements with the busy bird this is an interesting take on the “Indonesian’ crisis. I do think there is a problem when writers still refer to East Timor when it is now officially named Timor Leste. It’s problematic for a few reasons, but mostly because it doesn’t get the most up to date information for the topic. All official documents refer to Timor Leste and researchers may miss the most important information by using the old terminology.

Despite this, Piping shrike puts ‘regionalism’ in its historical context, though the significance of ‘East Timor’ to the main relationship between Indonesia and Australia is definitely downplayed with “Even East Timor gets on board”. (With criticism of Australian security efforts) But Timor Leste has had long standing objections in the international court. (By way of the legal challenge to the Australia, Timor Leste Treaty provisions as they relate to oil and gas usage/revenues.)

End

“It’s not goodies versus baddies, it’s baddies versus baddies.” Tony Abbott on Australia’s foreign policy dilemma.

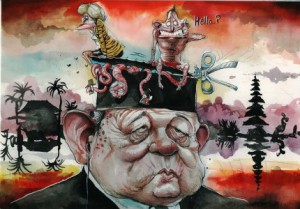

“Apology demanded from Australia by a bloke who looks like a 1970′s Pilipino [sic] porn star and has ethics to match.” Liberal media strategist

It’s getting hard to keep up. Government disarray, a non-existent honeymoon, and the most hostile media faced by any Liberal government in living memory have all meant the issues are now stacking up. On the international stage (let alone the domestic one) the Indonesia row has been overtaken by the Chinese row and now even East Timor feels up for having a go. Good grief.

This is all a shame. Since, in moving on from the Indonesia row, it has not yet been brought out that something very new happened during it. While everyone is sighing relief with the departure of Rudd and wanting to “move on”, the legacy of what he did in his last 100 days is proving harder to shake off.

The spying row exposed the phoniness of Australia’s “regionalism”. Indonesia is not Australia’s most important partner, the US is. Anything Australia does is seen through the prism of the only relationship that really counts in Australian politics. The exposure of Australia’s role as a listening post for the US in the region only exposes the reality that everyone already knows. So why was it so disruptive?

For a middling power, Australia’s foreign policy is unusual. It’s basically to be closely aligned as possible to whatever happens to be the leading global power of the day, whether the UK in the first half of the 20th century or the US in the second.

The downside of this has been Australia has been required to trot along to pretty well every global military venture dreamed up by these two (the 50s and 60s, when Australia was transitioning between them, was especially busy).

The upside is more subtle. Quite what it does for Australia’s world standing might be mixed given that Australia, especially in the region is often seen as just a mouthpiece of the US.

But the domestic benefits are pretty clear. It allows Australian politicians to present themselves as major players on the world stage when they’re not. In the Iraq war, Howard got away with presenting himself in the Australian media as one of an alliance of three, whereas to the rest of the planet there was Bush, and perhaps Blair, but Australia’s presence was unknown (on that note, try finding a Brit or an American who knew Australia was in Vietnam). It’s an act that Australian politicians are rarely caught out on, Howard’s slap down by Obama in 2007 a rare example.

This unusual foreign policy has a direct impact on the domestic scene. Historically, regional politics has little impact on domestic politics, except as much as they are seen through the prism of US/UK interests like the Vietnam War.

But nor do Australian politicians especially need to concern themselves with global events when there is no clear line from the leading power. The impact of the upheavals in the Middle East, for example, a major headache for the US political class on how to respond, has required the Australian response, as Abbott’s comments on Syria show, to barely need rise above the moronic.

The end result has been to lend Australian politics a curious impervious air for a middling power that appears at most times to be unaffected by the world around. It gives the illusion that everything emanates from Canberra, deeply flattering for what is otherwise a fairly ordinary political class.

In the last few decades, politics has taken a regional turn usually when the US has changed or lost direction and Australian politicians have had to pick up the slack, such as during the late 1960s and early 70s when US foreign policy had to adapt the failing war in Indochina. It prompted the US to tone down the Cold War and seek rapprochement with China partly in a bid to help stabilise the region with Whitlam famously pre-empting Nixon’s visit to China in 1971.

Generally Labor has proven more flexible on such shifts, with the Coalition preferring the clear polarity of the Cold War. The lack of clear direction from the US in late 1970s caused headaches for Fraser, with his Foreign Affairs Minister, Peacock, resigning and challenging him over what, for most Australians at the time, was the fairly arcane issue of UN Recognition for Pol Pot (that nice Mr Fraser wanted it).

It was a similar story during the next period of “regionalism” when the Cold War finished properly at the end of the 1980s. Keating promoted regionalism as one his “three R’s” but, like most of Keating’s post-Accord initiatives, owed more to political will than reality. Nevertheless Keating claimed that Howard would be a risk in Asia, especially following earlier comments on immigration. Howard almost proved it over East Timor.

While Keating was doing the talk on regionalism, Howard’s East Timor intervention in 1999 could be truly called a regional initiative. Perhaps more than Howard wanted. After having his bluff called by Indonesia’s President Habibie on holding an early referendum, Howard was left swinging in the breeze by Clinton with priorities elsewhere.

But even in East Timor, Australia acted more like a US surrogate than a regional player. It mirrored US policy at the time that was encouraging UN/NATO intervention in hotspots around the world especially in Eastern Europe. It did some good for Australia’s standing on the world stage, but little good with its neighbours, especially Indonesia.

The fall-out was apparent in Indonesian cooperation on asylum seekers. By 2000 – 2001 boat arrivals were spiking to what were then record levels, made worse by the introduction of TPVs in 1999. As Ruddock noted later, Indonesian cooperation only resumed after 9/11, consolidated by the Bali bombings, and managed around the Bali Process.

The War on Terror briefly brought some of the political benefits of the Cold War both domestically and internationally. It allowed Howard to strut the world stage for the benefit of cameras at home and turned the leader of a floundering government into the Man of Steel we have since come to love.

When the War on Terror faded so did the political benefits and the framework for regional affairs. The Bali Process was quietly dropped and the toning down of rhetoric on asylum seekers and the dumping of the Pacific Solution was initiated by Rudd, but followed by the Liberals as a pragmatic response.

The retrenchment of US leadership under Obama led to the third attempt at regionalism that, at first started less convincingly than the others. When Rudd came to power his intention was to adapt to US retrenchment by acting as go-between the US and China (like it was needed) and pursuing that agenda where US interests were less clear, climate change.

But as Rudd found in Copenhagen, no US leadership means no leadership at all. The detaining of a businessman in 2009 showed Australia had little real influence with China, and Oceanic Viking showed no leverage with Indonesia. By Gillard’s turn, we had Australia not even able to get East Timor to agree to a detention camp and the High Court knocking down a Malaysian Solution at home. By 2012, regionalism and Gillard’s chances of re-election were dead.

Then Rudd returned. When he did, he brought in a new “regionalism” but of a type Australia had not seen before.

It is possible to pin point exactly when this new regionalism started. it was 4 ½ minutes into Rudd’s 730 interview on 6 June when he pointed out what had been obvious for a long time but barely mentioned in either politics or the media – Indonesia would not allow the Coalition’s “turn back the boats” policy to happen.

It seems hard to believe now, but this point had been rarely made before, not least because Labor didn’t want to appear to be giving the impression that stopping the boats was not really an option.

More disconcerting was that by raising the issue of Indonesia’s attitude, Rudd was directly flying in the face of Howard’s mantra that “we will decide” who enters the country – an act of post 9/11 bravado that concealed the intense regional efforts Howard, Downer and Ruddock were making at the time. What Rudd did was to bring the importance of regional cooperation into the public arena and into one of the most important domestic issues for Australian politicians (if not as important in the electorate).

In doing so, Rudd was exploiting a weakness of Abbott and Gillard who had both made asylum seeker policy a central issue and were pretending that it was possible to go back to Howard’s post 9/11 policy. But the driver for both of them doing so were internal reasons in their respective parties (Labor’s insecurity over its base and the Liberals’ “branding” worries) – but without the post 9/11 conditions that had helped Howard and Downer get Indonesian cooperation.

But by raising Indonesia’s attitude to the Coalition’s boat policy, Rudd did more than just score a political point at Abbott’s expense. It became clearer in one of his earliest press conferences after resuming the leadership when he again raised the Indonesian objections and the possibility of diplomatic conflict and underlined the point by mentioning Konfrontasi.

Rudd’s allusion to when Australia joined Britain in the early 1960s in a military intervention to support what was effectively the British protectorate of Malaya against Indonesia, caused uproar from the right, and for good reason. First, because it highlighted the dubious historical record of Australia’s “regionalism” that was generally conducted on behalf of more global interests. But secondly it also gave the moral edge to Indonesia in the boat issue in what is seen by them as an issue of sovereignty.

What Rudd did was to give a green light, and considerable leverage, to do what no regional country had really done before, intervene directly into Australian domestic affairs. To drive the point home, the Indonesian Foreign Minister was paraded in front of the media to repeat a message that had been ignored for years.

The domestic benefits to Rudd were immediate: polls showed a sharp fall in the Coalition’s advantage on the issue, although obviously we had to find out once again that it was never the vote changer that some think.

But the more lasting consequence was the leverage it gave to Indonesia to get at the Coalition, which was stepped up a notch when the spy story broke. Despite the calm façade, we probably had a glimpse of what was going on in the right behind the scenes with the public self-immolation in social media of the Liberals’, er, media strategist. But while the right’s histrionics were at least clearly grasping what Indonesia was up to, the response from some on the left was more insidious.

It was summed up by a piece by academic Greg Barton in the Conversation, when comparing Indonesia’s response to revelations of spying by Australia and Germany’s response to US spying, he wrote:

… while Abbott might share in common with Obama a certain cool, precise, rational style of communication, Yudhoyono is an Indonesian president, not a German chancellor. For Yudhoyono, as his stream-of-consciousness Twitter feed has made clear, the problem with Abbott’s eloquent response is that it lacks emotional substance.

Leaving aside the rather unpleasant undertones of cool and rational versus “emotional”, Barton sums up the general view on the left that Indonesia has been wronged and Australia, as a bit of a bully, owes Indonesia an apology.

A comparison to Germany is indeed apt. Both Germany and Indonesia would have been fully aware that they were being spied on for years and hardly surprised by the revelations. How much a deal they make of it depends on what they want to do with it. In Germany’s case, the spying revelations give it a rare opportunity to take the moral high ground with the US to push the relationship more to its advantage. For Indonesia, a similar story applies, as was astutely summed up by the Fairfax Indonesian correspondent.

The difference is who they are targeting. US decline tends to get exaggerated but Germany, now consolidating its leadership in Europe, can take advantage of the current uncertainty in US foreign policy to press an advantage. But for Indonesia, an emerging economic power, the US’s deputy in the southern Pacific is a much easier target.

Merkel would know there is little leverage in US domestic politics with even the liberal US press unapologetic about the more intrusive aspects of its global role. But for SBY, whatever his emotional state, going on Twitter (in English) makes perfect sense as he would know, as a Liberal media strategist seems not to, that the Australian media would be all over it and generally only too happy to use it to cause further embarrassment to a new, weak government.

The left have been portraying Indonesia as the victim and Australia as the bully but the reality is more the reverse. For a country with a past of pontificating and interfering in the affairs of its neighbours, the growing weakness of its political system means it’s payback time. Welcome to the new, real regionalism.

Recent Comments