Monday, December 16, 2013

A response to Barry York’s article, Can we have a real Education Revolution?

Barry commences by pointing out that class size has reduced from 50 to 25 over a generation.

It is often claimed, by the political right, that reduction in class size hasn’t improved educational outcomes. The statistics support this position of the right. John Hattie has become an often quoted authority about effect sizes:

“… a synthesis of meta-analyses and other studies of class size demonstrate a typical effect-size of about 0.1–0.2, which relative to other educational interventions could be considered ‘‘small’’ or even ‘‘tiny’’, especially in relation to many other possible interventions—and certainly not worth the billions of dollars spent reducing the number of children per classroom. The more important question, therefore, should not be ‘‘What are the reasons for this enhanced effect-size?’’, but ‘‘Why are the effect-sizes from reducing class size so small?’’”

– Hattie, J. (2005).The paradox of reducing class size and improving learning outcomes. International Journal of Educational Research, 43, 387–425

I believe that the Gonski report is yet another iteration of this process. It throws money at schools but lacks an evidence-based plan to actually improve educational outcomes.

Barry fondly mentions “a wonderful History teacher by the name of Itiel Bereson”. I agree that great teachers make a difference and that this is far more important than class size.

I also agree that the teachers union plays a very limited and sometimes negative role in real educational reform because they are more interested in teacher conditions than teacher quality. I’m angry at the Union for not supporting performance pay for teachers in remote indigenous communities, conditional on them achieving measurable improvements. If the teachers union had responsibility for determining the nature of teacher training in Universities then they would feel more pressure to actually come up with an educational approach that works, rather than focusing too narrowly on teacher rights.

But when Barry argues that classroom teachers “know best” there is some lack of the clear thinking he extols beginning to creep in. If there are only a few great teachers like Mr. Bereson, one wonders why they as a group “know best”? Barry is expressing the belief here that those who do the real work, those at the chalk face, as a result of their nitty gritty day to day experience, “know best”. Yet, if they really know best why do they support a union that focuses on worker conditions, promotes the same green issues that Barry objects to and doesn’t push hard enough for quality teaching?

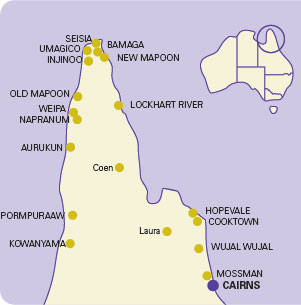

Who really does know best? One group that I have been taking a lot of notice of recently are those who promote evidence-based criteria and have the skin in the game of actually working with and improving the learning of disadvantaged students. In Australia, this would include Kevin Wheldall, Robin Beaman-Wheldall and Kerry Hempenstall as well as the initiative promoted by Noel Pearson in Cape York, using the American derived teaching materials of Zig Engelmann.

Barry goes on to counterpose Learning to Teaching as though there is no real connection between them. Moreover, he claims that the social purpose of schools is to imprison the mind and that hasn’t changed for two centuries. This is simplistic argument. As always, the devil is in the detail.

This leads into Barry arguing for the end of learning as we know it and it’s replacement with learning over the world wide web. We are led to believe that we can do this now because in C21st we have a “very high literacy”. If only this were true. Unfortunately, the literacy rate in Australia leaves much to be desired. Although it has improved massively since the late C19th, the really important measure is whether people have sufficient literacy to be highly functioning members in today’s society.

My research indicates that roughly 44% or 13.6 million Australians aged 15 to 74 years have literacy skills that will make it difficult for them to independently extract useful information from the world wide web (source: Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies, Australia 2011-12

Moreover, Australian schools are not doing a very good job in teaching basic literacy. The PIRLS 2011 study into reading comprehension put Australia second bottom of all English speaking countries surveyed. 24% of Australian students had a Low or Below Low score in reading comprehension. See Kevin Wheldall’s article, PIRLS before Swine for more detail.

The basic problem is that teachers have not been trained properly to teach literacy. This was the conclusion of the Brendan Nelson National Inquiry into the Teaching of Literacy in 2005 but none of the recommendations from that inquiry have been implemented. The real villains here are the teacher trainers in universities and the teacher unions who block reform. (the education establishment). Many of them are still wedded to discredited whole language approaches.

It has been argued that there are other, more modern forms of literacy than old-fashioned “reading comprehension”. These arguments sometimes take the form that it is more important to “read the world” than read the word. But a little thought is enough to convince most people that old fashioned “reading comprehension” is a prerequisite to “really learning” on the Internet.

So, the statistics reveal that at least 44% of adult Australians and 24% of young Australians, still at school, are going to miss out if Barry’s model of school reform is implemented. Of course, the internet has incredible learning potential for highly literate and self motivated learners. But Barry has made too many sweeping generalisations in his historical and social analysis of the actual nature of schools. If you are not clear about the actual problem then how can you be clear about a viable solution?

Is it possible to conceive of a useful purpose for schools? Yes, it is. Anthropological findings show that there is no easy or natural path to certain types of knowledge, including reading and writing. This type of knowledge has been called non universals (by Alan Kay) or “biologically secondary cognitive abilities” (by David Geary).

Universal knowledge, displayed by every human tribe, includes such things as:

social

language

communication

culture

fantasies

stories

tools and art

superstition

religion and magic

case based learning

theatre

play and games

differences over similarities

quick reactions to patterns

loud noises and snakes

supernormal responses

vendetta and more (about 300 of these have been identified across cultures)

The above categorises the level of what most people do on the world wide web (social media), despite it’s potential for higher learning.

On the other hand, the non universals include such things as:

reading and writing

deductive abstract mathematics

model based science

equal rights

democracy

perspective drawing

theory of harmony

similarities over differences

slow deep thinking

agriculture

legal systems

These are much harder to learn than the universals because we are not directly wired to learn them. These things are actually inventions which are difficult to invent. And the rise of Schools going all the way back to the Sumerian and Egyptian times came about to start helping children learn some of these things that aren’t easy to learn. For more details about the universals and non universals see The non universals

Some things are hard to learn. Although that hard to learn information is on the internet it is usually not sought out spontaneously by your average facebook junkie. I call the popularity of social media the you_twit_face phenomena (after youtube, twitter and facebook). Pop culture is the main form of discourse on the internet.

Learning to read is rocket science. But once you know how to read you totally forget the process you went through to learn to read. The literate then become blind to the plight of the illiterate. The idea that reading is natural, you just soak it up naturally from the surrounding environment, is BS.

The legitimate purpose of school should be to teach the non universals, the things which are not learnt naturally. That is one reason why schools were invented in the first place. They are not simply vehicles to imprison our minds.

Barry quotes Mao: “If you want knowledge, you must take part in the practice of changing reality”. I can agree with the Mao quote but like any one liner it only represents a part of a more complete picture. Mao argued for an ongoing spiral of knowledge between practice and theory. If you are going to take part in the practice of changing reality then you had better also be prepared to study / research hard and acquire a lot of knowledge, including book knowledge. We all know activists who end up doing and thinking foolish things.

In fact, there are many former radicals from the late 60s who went onto become education establishment leaders and union activists promoting non authoritarian, constructivist teaching methodologies such as whole language that have led to a quarter of our students not becoming literate. They have changed reality in a bad way due to insufficient research informed by an intuitive dislike for a form of “authority”, mistaking authoritative with authoritarian.

The factory model critique is problematic when applied to education because there is some good education that fits a factory model type of metaphor. Factories in capitalism are bad because they steal from the labour of workers. Another sense in which it is used is the replacement of artisan labour with mechanical labour, but that critique is more problematic according to Marx. There is nothing wrong with a machine replacing what was previously done by an artisan.

Many intelligent people report bad experiences at schools. For example, they were told to do things, such as write answers in sentences, over and over again, something that they already knew how to do and so the experience was boring, boring, boring …

But, could you have a good factory model in an educational setting? In my opinion, yes. One answer here would be to improve the factory, each student having their own individualised, computerised assembly line programmed to help achieve both essential literacies but also electives beyond the basics.

Another popular, related argument is that individuals have multiple intelligences or different learning styles, which have to be catered for. But those positions have pretty much been abandoned by thinking educators. Lookup Dan Willingham on the net, he is very good at debunking both of those fads (multiple intelligences, learning styles)

Direct Instruction is pretty much a factory model, a far better factory model than what happens in most existing schools, and so the intuitive dislike of it by “progressives” is strong – but wrong. In teaching basic literacy and maths the research shows that one method fits all is a very good way to go. Kevin Wheldall calls this Non categorical teaching.

In conclusion, what is my idea of a good argument for school reform? It’s a matter of getting the balance right between components that need to be highly structured and other components enabling freedom of expression. Thanks to people like the Wheldalls (MULTILIT) we now know how to achieve very close to 100% literacy education through a structured approach, an individualised factory model if you will. Direct Instruction models could also be beneficial for highly literate people wishing to extend their knowledge over particular domains, eg. the contribution of Einstein to our knowledge of physics. Beyond that I agree that Barry’s ideas have merit. The internet has much potential for extending our knowledge further for those who are literate and motivated to do that. But as Mao also said, you have to lift the bucket from the ground, not start in mid-air.

Recent Comments