Question “The only experience that I have with dialectics is a horrible essay that I had to write at university about Mozart and Beethoven. I’ve never really understood what dialectics means, except that it’s a great word to use when pretending to be intellectual over a cup of coffee. Most other people don’t really seem to understand the concept either, but would prefer not to admit it. I know this as I regularly drop it into conversations and no one has pulled me up on it yet.. see emperor’s new clothes post!”

Dialectics – What is it, what are examples of it?

by Keza 2004

I mentioned in The relation between materialism and idealism topic that materialist philosopher Daniel Dennett doesn’t mention the word dialectics – so in reading Dennett I’ve been looking out for what language he uses when describing concepts that are dialectical.

I’ve found one instance – he uses words like paradoxical to describe the problem and then in detailing his solution says things like, “this is not paradoxical at all”

An example is that Mother Nature / Evolution has no foresight and yet has managed to create humans who have foresight.

• Re: progress and dialectics

Posted by keza at 2004-12-28

The best laid plans of mice and men…. if practically everything that we do results in something not intended then why do we plan, why do we struggle, why do we try to move the world in a certain direction?

When Engels wrote that consciously willed actions often result in quite unintended consequences I think he was disputing the Hegelian idea that history is “the gradual realisation of ideas”. His point was that what happens in history comes about not as a direct result of abstract ideas, wishes, intentions (and so on) but is governed by ‘inner laws’ – ie what is possible (and therefore real and rational) in a given epoch. Movements don’t arise just because someone comes up with a good or bad) idea and manages to convince lots of people to follow them. Movements for change arise out of material conditions – the possibility for change is present and that opportunity is seized. The ideology in which the movement is clothed is (somewhat) secondary.

“The distinction should always be made between the material transformation of the economic conditions of production … and the legal, political, religious, aesthetic or philosophic — in short, ideological — forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out.”

Marx: Contribution to the Critique of Political Philosophy (1859)

An example is the idea of “equality” in the bourgeois democratic revolution. The idea that “all men are created equal” stood in direct opposition to the feudal belief that all men are most definitely not created equal. The growth of capitalism made it not only possible but also necessary for the idea that rulers are made rather than born to take hold. Thus on a conscious level the motivation for bourgeois revolution was belief in ‘liberty, equality and fraternity’ but at a more fundamental level, the revolution was driven by the necessity to liberate the productive forces from the constraints of feudalism. That reason (or motivation) was only dimly appreciated however.

Friedrich Engels wrote in 1893 that:

“Ideology is a process accomplished by the so-called thinker. Consciously, it is true, but with a false consciousness. The real motive forces impelling him remain unknown to him; otherwise it simply would not be an ideological process. Hence he imagines false or seeming motive forces.

I don’t think this means that bourgeois revolutionaries didn’t really believe in liberty, equality, fraternity – or that the battles they fought weren’t really for these things. We all know (except perhaps for the pseudo left) that as a result of the democratic revolution we have freedoms and rights that were hardly even dreamed of previously. However the ideas themselves weren’t the driving force – these ideas could only take hold because the material conditions were crying out for them (so to speak).

I think what bothers a lot of people is the feeling that perhaps this means that what they as individuals actually do doesn’t really matter – that somehow we are all carried along by a tide of “underlying forces” , that we are seized by ideas rather than seizing them ourselves etc etc. Engels refuted this when he said “freedom is the recognition of necessity” (Anti Duhring?) … once we come to understand “how things work” – “the rules of the game” then we do have a real chance of using our understanding to influence the course of history. Engels’ Letter to Franz Mehring in Berlin is interesting in this respect.”

He starts by pointing out that both he and Marx tended to neglect the role of ideas/ consciousness in bringing about change…

“Marx and I always failed to stress enough in our writings and in regard to which we are all equally guilty. That is to say, we all laid, and were bound to lay, the main emphasis, in the first place, on the derivation of political, juridical and other ideological notions, and of actions arising through the medium of these notions, from basic economic facts. But in so doing we neglected the formal side – the ways and means by which these notions, etc., come about – for the sake of the content. This has given our adversaries a welcome opportunity for misunderstandings and distortions…..”

and later:

“Hanging together with this is the fatuous notion of the ideologists that because we deny an independent historical development to the various ideological spheres which play a part in history we also deny them any effect upon history. The basis of this is the common undialectical conception of cause and effect as rigidly opposite poles, the total disregarding of interaction. These gentlemen often almost deliberately forget that once an historic element has been brought into the world by other, ultimately economic causes, it reacts, can react on its environment and even on the causes that have given rise to it.”

No time to write any more now!! I’ll finish with a quote I quite like though:

“Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like an Alp on the brains of the living…. “

(Marx: The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napolean)

end Keza

Posted by kerrb at 2004-12-19 01:54 AM

More about the usefulness of dialectics, being a bit more specific about it than in my previous reply to sally.

1) socialist / not socialist dialectic

A few years ago (maybe 20) I went to a debate where someone from the pro-Soviet so called communist party was arguing that the Soviet Union was still a socialist country. This person was so wrapped up in the details and scope of his argument that I could see that no single point could be made in question time that could possibly persuade him that he might be wrong. I wanted to support the case that the Soviet Union wasn’t socialist and so was racking my brains for a question that might get through, if not to the speaker, then at least to the audience.

What I thought of and asked the pro-Soviet speaker was: ” Are there any possible circumstances that might arise in the future which would persuade you that the Soviet Union was no longer socialist?”

To the amusement and bemusement of some of the audience, he replied, “No, the Soviet Union will always be socialist”

2) progressive / reactionary dialectic

I think a similar sort of point can be made to the pseudo-left in connection to the US invasion of Iraq.

In my view it’s pretty straightforward that the US has led a campaign to overthrow the fascist government of Saddam Hussein and is now proceeding to help Iraqis create a democratic government. That has to be progressive.

Because historically US Imperialism has been very reactionary, as exemplified by the Vietnam war and much more, there are now many people in the world who seem incapable of conceptualising that the US could possibly do something progressive. It’s always possible for these people to point to bad things that the US does – there is no shortage of examples.

Maybe part of the problem is that they have an ingrained black and white, non dialectic world view, which implicitly denies the very possibility that the US could do something progressive.

I’m not saying that thinking dialectically is a substitute for studying the details of processes in detail – including the details of what the Soviet Union became historically and the details of what is happening in Iraq and the Middle East. But that having the concept of dialectics (the coexistence of opposites in things) might help prevent falling into the rigid black and white thinking illustrated in the two examples above. If some people can’t even conceptualise that it might be possible for US Imperialism today to do something progressive then no amount of detail is going to change their mind about Iraq. Their thinking is dogmatically stuck at another level to do with their whole world view. I’m arguing that studying dialectics is useful because it helps us keep our minds open to these possibilities.

Here’s a paragraph from Dennett:

“One of the standard (and much needed) correctives issued to those who study evolution is the old line about how natural selection has no foresight at all. It is true, of course. Evolution is the blind watchmaker, and we must never forget it. But we shouldn’t ignore the fact that Mother Nature is well supplied with the wisdom of hindsight. Her motto might well be “If I’m so myopic, how come I’m so rich?” And while Mother Nature is herself lacking in foresight, she has managed to create things – us human beings, preeminently – who do have foresight, and are even beginning to put this foresight to use in guiding and abetting the very processes of natural selection on this planet. I occasionally encounter even quite sophisticated evolutionary theorists who find this paradoxical. How could a process with no foresight invent a process with foresight? One of the main goals of my book “Darwin’s Dangerous Idea” was to show that this is not paradoxical at all. The process of natural selection, slowly and without foresight, invents processes or phenomena that speed up the evolutionary process itself – cranes, not skyhooks in my fanciful terminology – until the souped up evolutionary process finally reaches the point where explorations within the lifetime of individual organisms can affect the underlying slow process of genetic evolution, and even, in some circumstances, usurp it.”

– Freedom Evolves, page 53

So, this illustrates that one can think dialectically without formally studying dialectics or even using the word dialectic. Dennett’s ability to do this would presumedly arise out of his deep study of the science of evolution combined with his materialistic philosophy.

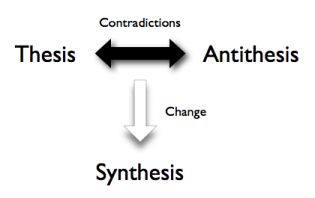

In dialectical language no foresight and foresight would constitute a unity of opposites and in the process of development one can transform into the other. I think this way of looking at it is preferable to Dennet’s apparent paradox that turns out not to be a paradox.

But it’s probably more important to really study the topic deeply (in this case, evolution) than just to be able to spout the magic words. But I also believe that it’s important to study dialectics itself (Mao, Hegel etc.) because this creates an awareness or sensitivity to possibilities of things turning into their opposite that we otherwise might not even notice – it has the potential to make our thinking more fluid and flexible.

end post

Posted by kerrb at 2004-12-19

Dialectics is the co-existence of opposites in everything, nature, mind, society. I’ll explain by reference to something said in The Emperor’s New Clothes thread:

Think of all the people scared to speak in public, or scared to admit how they feel about something, or someone! I know for a fact that my private side is very different from my public face. So in my opinion this is a ‘problem’ that stretches right across the board, it’s not just in intellectual circles. People in general are afraid to speak their minds! Me too, so afraid that I don’t want to post this, but I will anyway.

What you are saying here is full of dialectics IMO. You talk about fear of speaking out and feeling compelled to speak out coexisting in your mind. Both of these opposites co-exist side by side. In some circumstances the fear might be stronger and you don’t speak. In other circumstances the compulsion to speak out might be stronger.

I think it’s fair to say that these opposite tendencies exist in everybody and so we are talking about something that is universal.

So, by contrast, what would be a non dialectical way of looking at this? We might view some people as always speaking out, the sort of people we wish would shut up sometimes. We might view other people as never speaking out, the sort of people that we don’t know what they are thinking. We might form black and white opinions about people with these extreme tendencies and as a result lose our curiosity, for example, not notice that a normally garrulous person has gone quiet in certain circumstances.

But of course there are no people like either of these two extremes. Although some people speak too much and others hardly at all these are just tendencies across the spectrum of possibilities. In reality, the two opposite tendencies coexist within everyone.

I’ve just taken one example of dialectics here from something you wrote in order to explain the idea. But whatever you are thinking about or studying I would argue that you can always conceptualise opposites that coexist within that thing. At the least I think it’s a very handy way to think about things because it can open up new ways of looking at something.

Recent Comments