The following is lifted from Bloomberg.

This week, regular Libyan forces wearing crisp new fatigues and riding in Humvees took up positions in the capital, Tripoli, and ordinary Libyans ran into the streets to cheer the unfamiliar troops as liberators. The moment was extraordinary, because Tripoli had become a battle zone for rival militias, and few people knew the city even had functioning army units. Quietly, the U.S. and some allies have begun training regular Libyan soldiers. The public response shows why a bigger effort that’s now being planned is needed, and should be expanded.

In recent months, Libya has verged on being a failed state, as militias have run amok, kidnapping Prime Minister Ali Zaidan for a day and shutting down the country’s oil wells. (Last month, oil production fell to just 450,000 barrels a day, from a high of 1.6 million in July.) Last weekend, gunmen from the port city of Misrata killed at least 43 anti-militia protesters in the capital.

Many Libyans are sick of the chaos. And a total breakdown of governance in this North African country would be a nightmare for the region and for Europe. With about $60 billion worth of annual oil and gas exports to fund warlords and al-Qaeda affiliates, plentiful arms and uncontrolled borders, Libya also is a big concern for counterterrorism officials around the world.

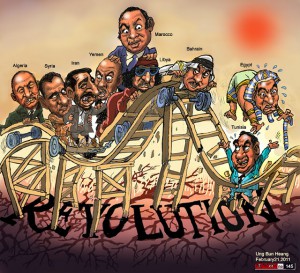

The lawlessness didn’t emerge overnight. The militias have been a problem since 2011, when they removed dictator Muammar Qaddafi, with an assist from North Atlantic Treaty Organization jets. Afterward, Libya’s weak government tried to disarm the revolution’s fighters. Then it tried to co-opt them, paying them to provide security. Neither approach worked; the militias have only grown more powerful, routinely storming the parliament to strong-arm legislators.

The international effort to train Libyan soldiers has barely begun. Should they have to fight today, the two Tripoli brigades that the U.S. appears to have been training would be no match for the militias. Yet the best and perhaps only hope for Libya and surrounding countries is that the tiny force can be expanded.

It’s taken long enough for Libya’s allies to understand this: The Pentagon recently said it would train, starting next year in Bulgaria, up to 8,000 Libyan troops for general purpose infantry duty. The U.K. will train 2,000 more troops at a base in Cambridgeshire. Italy, Turkey and France will also take part, pushing through as many as 15,000 personnel.

The European Union in May started a program to train Libya’s border guards, investing 30 million euros ($40 million) and 110 people. The U.K. and other nations are attempting to train police officers, and a small team of NATO advisers is to help build the security infrastructure to make all this work. In post-Qaddafi Libya, pretty much all institutions have to be built from scratch.

The international help has been slow in coming partly because Libya took this long to request it, but also because the situation in Libya is so chaotic, nobody is sure the training programs will work. The EU, for example, hasn’t been able to get a list of people to train for its border mission, and its trainers are stuck in Tripoli for security reasons. Large swathes of the country’s borders can’t be covered because the militias and local tribes that guard them now live by smuggling and don’t answer to the central government.

Yet Libya’s allies cannot let such obstacles or resistance from the militias be used as an excuse to slow or gut the training effort. Libyans themselves will need to do most of the work to make the program a success — from raising state security salaries above those paid by militias, to creating a national security council. A recent Carnegie Endowment paper has laid out the framework required.

At a minimum, Libya needs a security force sufficient to guard crucial government institutions, oil fields and sensitive border crossings, as well as functioning police personnel to provide local security in place of the militias. The popular response to Monday’s first outing by Tripoli’s nascent regular army, and the decision of the Misrata militiamen to withdraw from the capital provide a glimmer of hope.

From Bloomberg http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-11-19/free-libya-from-the-liberators.htmlCY93

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/26/world/africa/egypt-and-united-arab-emirates-said-to-have-secretly-carried-out-libya-airstrikes.html?action=click&contentCollection=Opinion®ion=Footer&module=TopNews&pgtype=article