Bigger version of map here

I was struck by an announcement from the World Bank about a book called Awakening Africa’s Sleeping Giant: Prospects for Commercial Agriculture in the Guinea Savannah Zone and Beyond that they have co-authored with the UN Food and Agriculture Organization

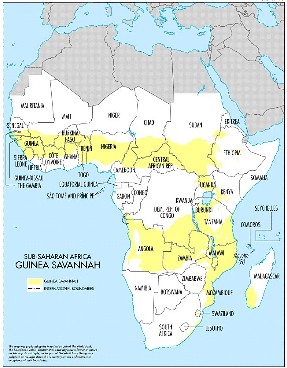

They are basically saying that if Sub-Saharan Africa can do in the vast Guinea Savannah zone what Brazil has done in the Cerrado and Thailand in its Northeast Region, it can vastly increase agricultural production.

Shown in yellow on the map, it is comparable in size to the EU, or half of Australia, Canada or the 48 States. Currently only about 10 per cent is used to grow crops. (source)

Agriculture has to expand dramatically if they are to become a net exporter of agricultural products while managing with a population that is expected to increase from 800 million to 1.5 billion before stabilizing later this century.

To me that looks like the need for a fivefold increase in output. There would have to be at least a two-fold increase in per capita food consumption if the people of the region are to chow down much like everyone else. Then they have to reverse their current position as a net importer.

Political and economic conditions will dictate the pace of this and other development in the continent. We can expect the greens and “NGOs” to run interference.

There is no free pdf version of the book. This is typical of the World Bank and UN agencies.

There’s a 4pp version here (among huge collection of searchable online docs they do provide).

Yep, Africa has enormous potential but I can’t see any sign of it shaking off the corruption, appalling governance and ethnic friction that make much of the continent a hell hole.

Presumably US and EU farm subsidies are a significant barrier to African farm exports.

There are some hopeful signs of many African countries improving governance and of a “new mood” for democracy among the people. The ‘new mood’ quote is from Hania Fahan, who heads the Mo Ibrahim Foundation’s research unit. Fahan reckons “the democracy genie is out of the bottle… There will be violent ructions and eruptions, like Kenya or Zimbabwe or Nigeria, but the trend is there, and it is remarkable. Africans want their rights, increasingly they are getting them”.

How can such a generalised statement be made? Well, Fahan’s research department surveys the governance of African countries against 57 criteria based on safety and security, rule of law, transparency and corruption, participation and human rights, sustainable economic opportunity and human development.

The Foundation’s survey found that governance is improving in 31 out of 48 sub-Saharan countries, with human rights being the area improving the most.

The report also found that the rise of the demand for greater democracy was part of the decline of the old “African Big Men” who ran, and run, their countries autocratically.

I came across the above information from a report in Time magazine, published in October 2008. It can be read here: http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1847585,00.html

The article also points out that the IMF estmiated (at that time) that Africa was likely to exceed economic growth of 6 percent. (I wonder how that has shaped up?).

Also, the OECD had reported that most of the money going into Africa since 2006 had been entrepreneurial investment rather than aid. Another good sign, I would think.

The Mo Ibrahim Foundation is funded by, and named after, the entrepreneur who established a pan-African mobile phone company in 1998. At that time, there were two million mobile phones in Africa. When Ibrahim sold the company in 2006 there were 100 million mobile phones in Africa.

So, things are moving…

For further evidence of Africa shaking off the bad old days and ways, there’s a site called Africagoodnews: http://www.africagoodnews.com/democracy/the-march-of-democracy-in-africa.html

The above link contrasts African countries today to the situation in the 1970s with free and fair elections. In the 1970s, only three African countries held elections; today 40 countries hold them (though not all are free and fair, but the trend is there).

Another heartening trend is that of countries constitutionally limiting the terms of their presidents and establishing independent electoral commissions to monitor elections.

Freedom House, which analyses freedom in countries against a set of criteria, concludes that eleven African countries are free today and 34 are partially free – compared to three and ten in 1972 and four and 18 in 1990.

Reasons to be cheerful!

I think your on the right track here Barry as African economic growth over the last decade was the big under reported story. Also pleasing to see is a report in todays Australian where the Indian government is planning to provide electricity to every village in India, these arnt strange times as much as they are great times for world development.

Melaleuca I do think that you have a good point about US and EU farm subsidies that squeeze African farmers out of the market. About time that our US and EU friends embraced free markets instead of just lecturing others about free trade.

The EU/USA subsidize their farming sector to the value of about a billion dollars a day.

In chapter 4 of David McMullen’s excellent book, ‘Bright Future’, there is discussion of Africa. He says: “Africa would also benefit from the US, EU and Japan opening up their markets more to agricultural imports. At present they are heavily protected. With the opening up of trade, it would not take long for some farmers to move into producing the crops and livestock desired by these markets. Furthermore, the elimination of the high protection of processed food could see food-processing industries develop in Africa”.

I also like David’s use (coinage?) of the term ‘kleptocratic’ to describe those autocratic African leaders who oppress their people and hold back economic growth in their countries. He says: “The most notable feature of Sub-Saharan Africa is that the ruling cliques who control most of the wealth are nothing remotely like a capitalist class. Their primary aim is the consumption of capital rather than its accumulation. They have found a host of ways for ensuring that funds that ought to have been devoted to economic development are wasted. In this they are reminiscent of the rulers of ancient Rome or Egypt, and nothing like a modern bourgeoisie”.

Their overthrow – and support for the democratic movements in the various countries – is essential.

The full chapter 4 is on-line at: http://brightfuture21c.wordpress.com/2007/01/25/chapter-4-capitalism-the-temporary-tool-of-progress/

The section on Africa is here:

Africa: More Capitalism Please

The most notable feature of Sub-Saharan Africa is that the ruling cliques who control most of the wealth are nothing remotely like a capitalist class. Their primary aim is the consumption of capital rather than its accumulation. They have found a host of ways for ensuring that funds that ought to have been devoted to economic development are wasted. In this they are reminiscent of the rulers of ancient Rome or Egypt, and nothing like a modern bourgeoisie. Like the ancients that they emulate, they have both domestic and external sources of wealth. Locally they engage in the time honored practice of screwing the peasant through either heavy taxation or compulsory crop acquisitions at below market prices. From the outside world, instead of tribute from vassals, they receive aid, loans and resource royalties. Funds are then spent on palaces and luxuries, on prestige projects that make no economic sense or diverted into Swiss bank accounts and various offshore investments. The term ‘kleptocrat’ has been coined to describe this class of people.

The wealth looted by some of the rulers has been staggering. People like Mobutu in Zaire, Moi in Kenya, and Babangida and Abacha in Nigeria, all amassed fortunes worth billions of dollars. Typical in extravagance was Mobutu who ruled Zaire from 1965 to 1997. He built about a dozen palaces and even linked some of them with four-lane highways. He also acquired grand estates and chateaus in Belgium, France, the Ivory Coast, and Spain, as well as vineyards in Portugal.[1]

Like the emperors of Rome and Pharaohs of Egypt, they also wasted vast resources on monuments to enhance their prestige and impress the populace. The continent is littered with grand conference halls, new capitals and show airports. President Felix Houphouet-Boigny of the Ivory Coast in the 1980s built a $360 million basilica to match the best in Rome[2], while Nigeria’s generals wasted billions of dollars of oil revenue building a brand new capital at Abuja.[3]

Delusions of grandeur has also motivated a lot of what were ostensibly productive investments. They have tended to be big showy symbols of development that make no economic sense under the backward conditions into which they were introduced. They were not accompanied by the necessary development in other areas such as transport and power infrastructure, management and education. Factories were built that never produced anything. Vast amounts of sophisticated agricultural machinery were imported and then abandoned in the field when they broke down.[4]

Then we have the billions of dollars spent every year on the military to provide the wherewithal for competing parasitic elites to fight over the loot. These are often from different tribes or ethnic groups.[5]

These kleptocrats are not totally spendthrift because they also squirrel away billions. However, even these funds have not been put to productive local use but instead exported for investment in the rich world – Swiss bank accounts being a favorite destination. The amount of capital which has fled the continent is staggering. The capital held by Africans overseas could be as much as $700 billion to $800 billion.[6] This exceeds the more than $500 billion in foreign aid pumped into Africa between 1960 and 1997.[7]

The techniques for siphoning off wealth are many and varied. The least imaginative is to pay yourself an horrendously large salary. In the case of Mobutu, his personal budget allocation was more than the Government spent on education, health and all other social services combined.[8] This is not including the revenue from diamond exports which went directly into his pocket.

Contracts for major projects do not go to the lowest bidder but rather to whoever offered the largest bribe. In one notable case in the late 1980s, a contract for a hydroelectric dam in Kenya costing hundreds of millions of dollars was cancelled and bidding reopened when the winner refused to pay a bribe to a leading crony of President Arap Moi, the ruler of Kenya from 1978 to 2002. The eventual winner paid the bribe but put in a bid much higher than the original one.[9] When kickbacks on public contracts do not supply enough cash, politicians award themselves fake ones.[10]

Padding the cost of projects is another method of achieving the same outcome. For example, the Nangbeto dam project in Togo was costed at around $28 million. However, this was increased to $170 million so that funds could be diverted into the pockets of the ruler and his cronies.[11]

Anything requiring government approval can be the source of bribes. These include permits to do just about everything, and most importantly licenses and concessions for mining natural resources. In Nigeria, Abacha, who ruled until his death in 1998, ensured that no oil deal or decision was made without his approval and that always required a ‘fee’,[12] while Ghana’s Minister of Trade in the 1960s used to charge a commission for import licenses equivalent to 10 per cent of the value of the imports.[13]

Owning businesses can be particularly profitable when you are a ruler or high official. The numerous business concerns of President Arap Moi always managed to win huge government contracts and charge the state exorbitant fees and prices. He also owned a cinema chain with monopoly control over movie distribution in Kenya.[14]

Having privileged access to goods can be a good earner when you sell them on the black market. In Rwanda, President Habryimana ran lucrative rackets in everything from development aid to marijuana smuggling. He also operated the country’s sole illegal foreign exchange bureau in tandem with the central bank. One dollar was worth 100 Rwandan francs in the bank or 150 on the black market. He took dollars from the central bank and exchanged them in the exchange bureau.[15] In Zimbabwe top government officials used their influence to buy trucks and cars at the artificially low official price from the state-owned vehicle assembly company and then sold them on the black market for enormous profits.[16]

Fictitious external debt has reaped vast funds for corrupt officials, with ‘repayments’ going into their overseas bank accounts. At one time over $4.5 billion of Nigeria’s external debt was discovered to be fraudulent.[17]

The economic impact of kleptocrats is not confined to ripping off most of the wealth that should have gone into development. They also make it difficult for everyone else to be productive. Most horrific of all is the destruction from their civil wars which have ravaged much of the continent. In 1999, a fifth of all Africans lived in countries battered by wars, mostly civil ones.[18]

Whatever limited infrastructure such as roads, schools, hospitals, power telecommunications is not destroyed in wars has often been allowed to deteriorate. Once bribes have been extracted at the construction stage, kleptocrats do not care if the resulting infrastructure falls apart through lack of maintenance. Besides, money for maintenance is money that can go into their pockets. Zaire (now Congo) was a classic in this respect. Agricultural produce intended for market often rotted on the ground because the transportation system had broken down. While the country had 31,000 miles of main roads at independence from Belgium in 1960, by 1980, only 3,700 miles were usable.[19]

Just registering a business in Africa is an ordeal. In a typical developed country it generally takes a day or two and costs a few hundred dollars, but in Africa it involves long delays and high costs. In Congo for example, it takes about 7 months, costs close to nine times the average annual income per person, and firms must start with a minimum paid-up capital of more than a third of that exorbitant fee.[20] Furthermore, the poor legal framework in which businesses try to operate adds to the cost and unpredictability of running a business. Soldiers and police often feel free to impose their own impromptu forms of ‘taxation’ and trucks carrying goods are constantly stopped at road blocks by police who help themselves to some of the load. Governments can behave in all sorts of capricious and discriminatory ways. Property might be seized or a firm’s license to operate suddenly revoked because the president of the country dislikes the owner’s political views or ethnicity; or you might discover one day that you are now in competition with a business run by the ruler or one of his cronies. Contracts are not readily enforceable because the courts are slow, expensive and frequently corrupt. As a result there is a strong tendency for businesses to deal only with people they know.[21]

The extremely low level of private foreign investment in Sub-Saharan Africa is a stark indication of how economically unattractive the region is. It gets about 1-2 per cent of the funds flowing into developing countries, and most of that goes to South Africa.[22] And of course the fact that the kleptocrats do not invest in Africa tells the same story.

Given the current state of Africa, modest progress is perhaps the best we can hope for over the next quarter century. Nevertheless, there are two positive developments particularly worthy of note that may bode well for the future: a number of countries have achieved some degree of democracy and political accountability; and there has been a drop in the extent of civil warfare.

In the 1990s a dozen political leaders were peacefully voted out of office – a previously unheard of method of departure. In 2004, 16 out of the 48 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa had governments that were described as democratic with elections and a level of civil rights for opponents of the government. Although in some cases the changes lose some of their shine when you take into account election rigging and the lack of independence of the judiciary and media, and neutrality of the armed forces.

In the last five years there has been a significant decline in the number of civil wars. The fighting has stopped in Sierra Leone, Angola, Liberia, Burundi, Sudan and Senegal. The war in the Congo is over, although marauders still plague the east of the country, and the one in northern Uganda appears to be spluttering out. These wars have been horrific in terms of deaths, devastation and duration. The death toll in the Congo was 3 million and in Sudan 2 million. The wars in Sudan, Senegal and northern Uganda lasted for two decades while in Angola even longer. This decline in internal conflict has been due to a mix of exhaustion, one side winning and external pressure. Where there is a victor, they are usually no worse than the vanquished and sometimes better. Whether this decline is temporary or long term remains to be seen given the potential for old conflicts to be rekindled and new ones ignited.

On the economic front, there is also the occasional bright sign. For example, a South African company has taken over the debt ridden and rundown government-owned railway line that runs from Kampala in Uganda to the Kenyan port of Mombasa. They plan to invest $322 million over the next 25 years overhauling the line and its rolling stock.[23]

If these tentative developments prove to be more than a false dawn, they can be attributed in part to the end of the Cold War during which the superpowers propped up those despots that aligned with them or bankrolled equally appalling rebel armies for the same reason.

Any progress will also be assisted by a transformation of the whole aid and lending regime. Historically, it has done nothing to help Africa. Not only have the funds been misused in the ways already discussed, but they have also helped to keep the kleptocrats in power. External funding makes it is easier for governments to be unaccountable and to withstand popular opposition. Luckily the World Bank was not around at the time to prop up bankrupts like Charles I of England and Louis XVI of France! When programs fail the usual response has been to attempt to salvage them with injections of even more funds, rather than to do a critical reassessment. In the case of lending this is made possible by the fact that the World Bank and other development banks are not commercial institutions that will go out of business if their loans do not perform. They are simply provided with more funds by rich country governments. Improving the situation has to mean a strong connection between aid and the quality of governance, and a far greater focus on helping agriculture, the main form of economic activity.

Democratic institutions need to be established that are more than a facade – there needs to be constitutions, elected government, civil liberties, the rule-of-law and the separation of powers. Dismantling some of the machinery of corruption is also important. This includes increased transparency in financial dealings and getting rid of regulations that only exist so that officials can be bribed to ignore them. The less progress in these areas the less aid.

The cancelling of external debts can be better handled in this context.[24] The regimes that are more likely to simply accumulate new and equally unsustainable debts are given less chance to do so. Where they are deprived of all new funds the extra scope for waste is limited to the debt repayments avoided which they now get to keep.

Agriculture is the predominant sector of Africa’s economy and is critical to its development. The sector has to retain the economic surplus it needs to introduce improvements and to move from communal (i.e., feudal or pre-capitalist) to private ownership of land. Africa would also benefit from the US, EU and Japan opening up their markets more to agricultural imports. At present they are heavily protected. With the opening up of trade, it would not take long for some farmers to move into producing the crops and livestock desired by these markets. Furthermore, the elimination of the high protection of processed food could see food-processing industries develop in Africa. A lot of humanitarian aid can also have the added longer term benefit of assisting agriculture. Efforts to reduce the impact of AIDS, malaria, TB and malnutrition not only reduce death and misery but ensure more people are well enough to perform productive farm labor. The necessary measures include new medical treatments, strengthened healthcare systems, higher yielding and more robust seed varieties and the development of farmer advisory services. Unfortunately, even programs directed specifically at the rural poor are not immune to corruption as evidenced by the many cases of medicines being diverted onto the black market. And no matter how well run, an assistance program has the problem that it may be freeing up local funds that would have been used for the purpose and which can now be wasted.

The dire state in Sub-Saharan Africa naturally prompts a ‘we must do something’ response. At the moment there is a rock star led campaign calling for debt forgiveness and large increases in aid.[25] There are also various studies and proposals circulating among rich country governments. While some of this concern is informed by the considerations expressed above, it could also rekindle the tendency to simply throw money around and repeat past disasters.

End

Just goes to show development and aid suck unless you owe them your life

http://www.economist.com/node/21555571